The events of the last two years have brought our political situation in much tighter focus, so I am going to go lighter on that side of the argument. I think most of my readers would now accept that we are in the long-term grip of a loose cabal of plutocrats who care about nothing but their own power and wealth, and have let everything else go to pot. So I will take it as my starting point that more public spending on these key priorities is a good thing and does not need an elaborate fact-based defense. If a measure is not as clearly or adequately spending on those priorities, though, I will note that.

There are no measures this year that I would recommend a “no” for those who want to do more to block trivial matters, or ones the Legislature can handle on its own – what I called the “anticlutter” recommendation in prior years. However, there is one where I will have a dual recommendation: it is probably a net good that it passes, but those in charge shouldn’t have let it come to the ballot in such a messy, questionable state.

Thanks for reading. Within a week I hope to have recommendations out for Oakland city/area measures. To be notified of these more reliably by email, sign up for my newsletter.

Quick-reference table:

|

Proposition Number and Title

|

Recommendation

|

|

Prop 1, Veterans and Affordable Housing Bond Act

|

Yes

|

|

Prop 2, No Place Like Home Act

|

Yes

|

|

Prop 3, Water Supply and Water Quality Act

|

Dual – Yes on impact; No on governance

|

|

Prop 4, Children’s Hospital Bonds

|

Yes

|

|

Prop 5, “Wealthy Aren’t Wealthy Enough” Act

|

No

|

|

Prop 6, “Let Our Roads Crumble” Act

|

No

|

|

Prop 7, Daylight Saving Time Repeal Act

|

Yes

|

|

Prop 8, Fair Pricing for Dialysis Act

|

Yes

|

|

Prop 10, Affordable Housing Act

|

Yes

|

|

Prop 11, Emergency Ambulance Employee Safety and Preparedness Act

|

No

|

|

Prop 12, Prevention of Cruelty to Farm Animals Act

|

Yes

|

(Prop 9? There is no Prop 9; that was the deeply embarrassing Three California Act, which was thankfully removed from the ballot by the courts, which determined it too large a change to legally take place without a constitutional convention or legislative referral.)

A. Housing: Yes on 1, 2, and 10; No on 5

Housing is a good example of how communities become unlivable when we neglect public goods and public solutions. Right now, in one of the wealthiest states in the country, in those same cities where so much new wealth is being generated, housing has become one of the biggest sources of financial and personal insecurity. Half of Californians spend more than 35% of their income on housing, and one-third spend more than 50%. Housing is not technically complicated: we have the land, we have the raw materials, we have the skills, we have the technology to put up however much housing is needed. So why haven’t we?

“The free market” is not an answer to the housing shortage. As Economics 101 should, but does not, teach everyone, an unfettered market will reach its own internal equilibrium, but there is no guarantee that that equilibrium will meet everyone’s needs. With housing construction and maintenance being largely a private matter, the government must monitor the housing landscape and, if the outcomes are not good enough or cheap enough housing for everyone, intervene to make it available, by some combination of public investment and private-sector regulation.

There was a time we did this. Starting in the New Deal, there was major public investment in housing, both state and federal. It was the federal government that invented the standard 30-year mortgage and still makes it possible to this day. The government also subsidized or directly built a great deal of apartment buildings and other multifamily housing. While of course this investment was deeply unjust racially, the investment on all fronts helped keep housing plentiful and fairly cheap, while also a huge step up in living conditions from before.

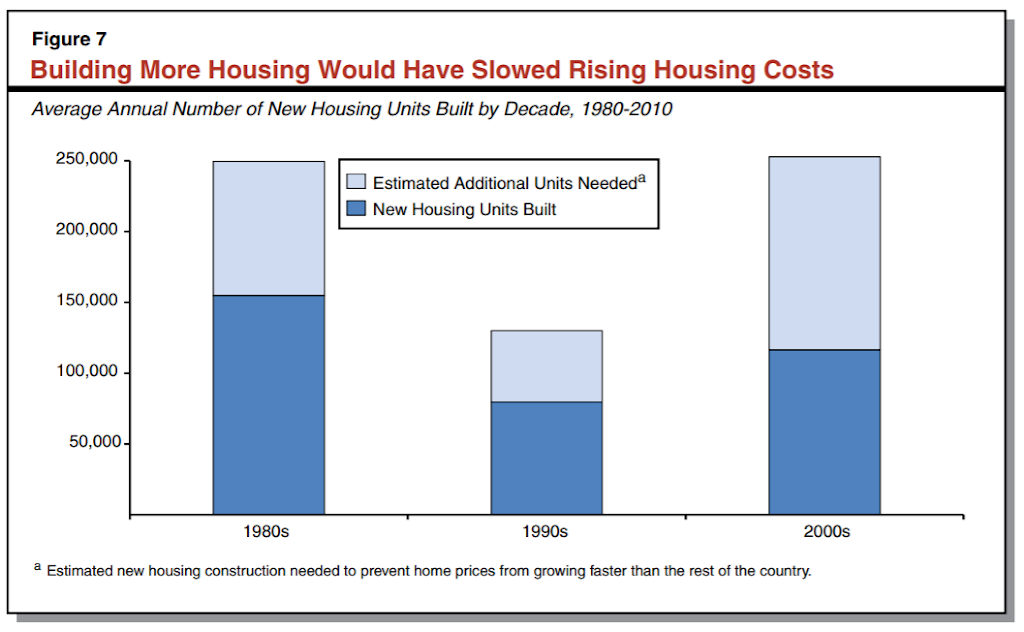

Then with the “tax revolt”, better described as the wealthy striking back, under Prop 13, Ronald Reagan, and the following generation, we stopped investing nearly as much in housing. And look what happened:

This shortfall in construction has continued since that graphic: from 2010 to 2015, we built an average of 50,000 new housing units a year; from 2016 to 2018, when the recession was over and the demand was obviously there, still just 80,000; and the state estimates that 180,000/year are needed just to keep pace with increasing population.

There are three propositions this year that would help this situation, and one that would hurt.

Proposition 1, the Veterans and Affordable Housing Bond Act: Yes

Prop 1 would pour some much-needed resources into making and retaining affordable housing. It would sell $3 billion in bonds to build or renovate affordable housing, as spent by the state housing department. It would enable many times that dollar figure to be spent on new housing by bridging projects that also use private, local, or federal funds.

Prop 1 has support from housing advocates of all camps; they all agree such investment is desperately needed. I also appreciate it because it focuses primarily not on building more single-family housing, but on building up multi-unit apartment developments in the denser building patterns we need – not huge tower blocks, most of the time, but rather the “missing middle” of 3-5-story buildings, as well as denser development around public transit. (You can achieve a surprising amount of density by letting this kind of development expand over a sizable area – the city of Los Angeles is far denser than Oakland, and that is one reason why.) It also has small but significant portions dedicated to farmworker housing and group-organized self-help projects like Habitat for Humanity. Portions may also go to making roads more pedestrian and bike-friendly, and enhancing parks, water, and sewers, as long as these improvements are part of denser development projects that need this infrastructure.

Prop 1 totals $4 billion, not $3 billion because the Legislature combined it with another proposal that spends $1 billion in veteran’s housing. This veteran’s bond is one like many that have been issued before: more traditionally, it just offers low-interest subsidized mortgages so veterans can buy their own homes (or farms) on better terms.

Not on the ballot, but a huge hindrance to building the housing we need is land use rules preventing virtually any increase in density in the areas where most people live. We have heavy rail stations almost entirely surrounded with single-family housing, an insane waste of resources. Due to a combination of bureaucracy and status-quo-loving residents, we have allowed a byzantine structure of barely accountable city-level restrictions to take hold. Many of the apartment complexes in the Bay Area would not be legal if proposed today.

As we seek to increase housing investment with Prop 1 and other efforts, we need to make the connection that aggressively supporting new housing supply is in fact a progressive principle. More housing is not the same as gentrification: more density lets both new migrants and existing communities persist side by side, in fact, without it, gentrification gets worse as everyone competes for the same limited supply. If you think of yourself as progressive or liberal, you should promote housing for all as a key principle, and accept that, as a tradeoff, the look of many cozy, well-off neighborhoods will change. If your first mental reaction to new development is your neighborhood is “Ugh, that’s ugly” or “Damn corporate developers” or “What about parking”, and especially if that’s how you’re inclined to speak out at the local level, please do some self-reflection about how that intersects with your other values. How can we drive emissions down if most of us still have to drive everywhere? And, are we in fact being welcoming to immigrants and refugees if none of them can afford to live here?

Proposition 10, the Affordable Housing Act: Yes

Rent control is another piece in the puzzle of solving the housing crisis. Right now, a state law, the Costa-Hawkins Act of 1995, bans cities from instituting rent control outside certain tight boundaries. There was a major push at the beginning of this year to repeal it in the Legislature, but this failed: Prop 10 is the same repeal measure that would restore cities’ freedom to impose rent control.

“Wait,” you might be saying, “don’t we have rent control in cities like Oakland and San Francisco? I’ve heard of it / I benefit from it myself; why are you saying it’s banned?” Yes, there are now 15 cities with a form of rent control that’s not banned, but they’re prevented from (a) controlling any buildings built after a certain date, mostly in the 70s-80s, (b) controlling rents on single-family homes or condos, and (c) controlling any unit’s rent when the tenant vacates it. The most immediate way many cities would take advantage of Prop 10 would be to make rent control kick in at a rolling date following construction: developers could charge whatever they want for the first 10, 15, or 20 years after construction, but thereafter rent increases are limited to inflation for continuing tenants.

This cause is puzzling to some people I know who pay attention to the economic arguments on the subject. Econ 101 supply and demand curves would predict that controls on prices would decrease construction; there are also semi-controlled studies finding such an effect in practice in San Francisco.

But the supply effect, if it exists, is not persuasive. We also have vast undersupply in the parts of the state where there is no rent control – that is, is most of it. Also, undersupply is so massive any negative impact from rent control would be a drop in the bucket – the study I linked suggested a 15% reduction, but that appears to have been a cumulative impact over two decades. So even taking the study at face value, it would independently reduce supply by less than 1% a year; but we build than half of what we should annually!

Direct action to increase supply by means such as public investment and legalizing density will increase supply by leagues more than rent control could decrease it. And our experience since ending most rent control in 1995 was that, to the extent it increased any supply, it was in the least socially effective way imaginable. Studies also show that rent control helps existing communities avoid being displaced, which makes perfect intuitive sense given current income inequality. In the short run, rent control will fill in some of the housing shortage gap, keeping the housing stock we have more affordable without public subsidy, and rolling dates will add more affordability over time.

In the long run, we need less reliance on markets and more use of social solidarity to make housing stable and fair. Lots of countries have huge percentages of housing provided publicly or by various kinds of social trusts. Housing can be plentiful and cheap, but only if we stop thinking of it primarily as a vehicle for making money, and treat it as the social infrastructure it is – a human right. Prop 10 takes us a bit further in that direction.

Proposition 2, the No Place Like Home Act: Yes

Proposition 2 addresses those most severely victimized by the housing crisis: people suffering homelessness. The best way to stop homelessness is to give people housing, no strings attached, regardless of substance issues or anything else. Without homes, people have none of the resources or mental space that give most people at least some chance to turn around their problems. Many of the people now homeless in California were brought there by high rents, which turned what might otherwise just have been job-searching intervals into downward personal spirals. Permanent supportive housing is a different kind of enterprise from the affordable housing funded by Prop 1, and needs its own programs and funding.

Prop 2 dedicates $2 billion to this cause, funding local projects that create permanent supportive housing units combined with mental health services, for people currently suffering or at risk of homelessness. The state will make grants to cities or counties based on competitive demonstrations of how effective their projects will be; cities will often need to add more funding to the projects. The LAO estimates it will add about 20,000 supportive housing units over ten years, which is nowhere near the full capacity needed (we have over 100,000 people suffering homelessness) but makes a big dent.

Prop 2 money already being collected, rededicating a portion of the millionaire’s tax passed in 2004 to fund mental health services. Many counties have left much of this funding unspent. In fact, the Legislature already tried to start this program using these funds in 2016, but someone sued the state on grounds that it contravened the 2004 initiative text which required the money be spent purely on new mental health services (one of the many operational hazards of ballot-box budgeting). Prop 2 was designed as a workaround: if passed, it will effectively be the people of California saying “No, we’re fine with this change, end the lawsuit and start the program right away.”

One principled argument out there against Prop 2 is that the state is not providing enough mental health services to begin with, and redirecting the money will perpetuate this. I’m sympathetic, and agree that it is likely not a lack of need but an excess of bureaucracy that keeps the money from being spent. At the same time, our resources are currently far skewed toward acute and critical care, and we need to put more focus on housing, social supports, and other preventive measures. This seems a highly reasonable step.

Proposition 5, the “Wealthy Aren’t Wealthy Enough” Act: No

I mention Prop 13 a lot partly because it’s symbolic of so much wrong with California, and created the harmful requirement of a supermajority for all taxes; but Prop 13 also broke the property tax system specifically. We theoretically charge a flat percentage of property value, but in fact, it’s effectively a percentage of value at the time of purchase, that assessed value growing at no more than 2% a year, no matter how much the house’s value might rise. That means if you bought a home 30 years ago, it will be taxed as, at most, 81% more, even if its value triples. But if someone else buys your house, their tax bill will reflect the true value – again, in the first year. The 2% growth has not even kept up with inflation.

Prop 13 was sold as helping low-income homeowners and retirees who might see tax bills rise when incomes did not, but in truth, it mostly helps wealthy homeowners who would otherwise pay the most tax – over 50% of the benefit to households making over $120,000/year (LAO). That is just on the residential side; corporations also get this treatment for their own property, however large.

In 2020, look for a measure to finally start reassessing values regularly for commercial properties – “split-roll”. Later, we also need to reform the residential side, because that too is deeply inequitable.

But right this year, Prop 5 is attempting not to reform Prop 13 but to supercharge it, make it benefit more wealthy people by an even greater margin. Since you get more benefit from Prop 13 the longer you keep a home, it creates extra incentive for people not to move. But more ballot measures in the 1980s, by the same anti-taxers, made the benefits “portable” to new homes in limited circumstances. Right now, once in your life, if you are at least 55, you can move a home of lower value, in the same county, and your tax bill will not grow. (Counties can individually choose to allow over-55s moving from another county this value-transfer; only 11 do so.)

Prop 5 says: let’s tear down those limitations and allow people to carry these low tax bills around forever. It keeps the 55-year minimum, but lets the transfer go to any county, for any home value, any number of times. So instead of Prop 13 tax limitations acting as a security measure in case people have trouble paying them, it becomes purely a reward for being old and well-off – meaning most often, white. It will also build up dynastic wealth, as other 1980’s measures allow low tax assessments to be passed down to one’s children and grandchildren.

The LAO estimates Prop 5 would cut revenues by a few billion dollars a year, much of that loss hitting schools. It was sponsored by realtors, because they thought it would help make the case against split-roll, which was expected to be on the same ballot, but ended up delayed. I suspect it was the realtors specifically because they know it would goose home sales and therefore their fees.

Prop 5 is utterly deplorable. It takes our existing travesty of a tax system more in the same direction, impoverishing our public resources for no benefit except an elite’s. Vote no.

B. Health care measures: Yes on 4 and 8; No on 11

Proposition 4, Children’s Hospital Bonds: Yes

Prop 4 would sell $1.5 billion to rebuild, refurbish, and equip California’s children’s hospitals. 90% would go to various named hospitals, while a small portion would be distributed among a larger group of hospitals that care for children with particular serious conditions under a specific subprogram of Medi-Cal.

In my opinion, children’s hospitals due to their constituency get perhaps an overly sweet deal compared to other hospitals and other areas of health care; however, it’s undeniable that they provide critical services, especially for some of the sickest children in the state. The seven main children’s hospitals treat about 62% of their patients via Medi-Cal, and that program is perpetually under strain. There have been bond packages similar to this one twice before in this century, but that money is now mostly spent, and there are plenty of further good causes to put it to: we’re on track to have virtually all hospitals seismically safe by 2020, but then by 2030 we’re supposed to have them all functional immediately after a quake. And the measure, although dedicated to specific hospitals, does not just gift them the money: a state authority has to approve the funded projects as reasonable.

Proposition 8, Fair Pricing for Dialysis Act: Yes

Prop 8 would impose price caps on dialysis providers based on costs. The market for dialysis treatment (for people with end-stage kidney disease) has been gobbled up in California by two behemoths, Fresenius and DaVita, both making billions in profits annually, paying out tens of millions in executive compensation, skimping on staffing and safety, and likely steering patients to better-paying insurance programs even when that meant worse benefits for the patient.

Monopoly or oligopoly is a failure state of the “free” market. Without policing, competition can lead to lack of competition, and at that point, all you have is unaccountable private power. The solutions are old but reliable: either split them up until there is real competition, or regulate their prices, practices, and profits until they resemble public utilities. Prop 8 is the latter. It would require dialysis providers to charge no more than 115% of their direct costs of care, meaning they would have to find room within the 15% extra for any administration and profit. (It’s very similar to the Medical Loss Ratio imposed on insurance companies by the Affordable Care Act, which made it difficult for them to profit by denying care.)

The companies being regulated are bad actors with bad track records, and their claims that the law will force clinic closures are not credible. They even have an escape route if parts of the law are overly aggressive: if they can prove in court the law does not allow them a “reasonable rate of return”, the courts can relax its limits as necessary.

It may indeed be the case that this measure was circulated by unions after the dialysis companies rebuffed their organizing attempts, but unionizing these companies would have been socially valuable, and so will this policy be. It is all part of making the state’s corporate class realize they are not in the Wild West. They can make money, but it will have to be with a modicum of social responsibility.

Proposition 11, the Emergency Ambulance Employee Safety and Preparedness Act: No

One rule of thumb from my experience with ballot measures is, Do not approve anything sponsored by a major corporation affecting its own industry. Prop 11 is written and pushed by the private ambulance industry and is dedicated to the proposition that they should be allowed to treat their workers more shittily.

Under labor laws, all employers have to give their non-exempt employees rest and meal breaks, but historically, ambulance companies would reserve the right to call out their paramedics or EMTs during those breaks, in which case their break would end immediately, they would be paid, and would get another break later to make up for it.

In 2016, the California Supreme Court ruled that this practice did not follow California labor laws as written. A break means a break, and you are not to be called out of it during that time. If the employer needs more staff to meet demand, let them hire them. After they ran out of appeals, American Medical Response wrote and paid for this proposition to come on the ballot, amending the law to allow this practice that is currently banned. (It also says the practice was always legal, canceling out any back pay the courts may otherwise demand of them.)

There is also a portion of the bill that requires new employer-paid training in responding to natural disasters, active shooters, and violence prevention for EMTs, as well as mental health services for the EMTs themselves. Ignore this – it is crafted to make the bill look like less of a handout to private interests.

AMR has now donated or loaned this measure $21.9 million, giving you an idea of how much they think they can make out of bad employment practices. If the “new” requirement were an intolerable burden on the state’s finances, they could have persuaded the Legislature to change the labor laws in this way, unions or no unions, but obviously they couldn’t. This is easy: vote no.

C. All other measures: transportation, environment, animals, and time itself

Proposition 6, the “Let Our Roads Crumble” Act: No

This measure revolves around the new gas tax, just as Prop 69 earlier this year did. To recap, finally recognizing we were chronically underfunding roads, transit, and other transportation infrastructure, the legislature finally passed by a bipartisan two-thirds vote a real increase in the state taxes on gas and diesel, as well as car license fees. The extra tax is 12 cents per gallon of gasoline; the extra fee ranges from $25 to $175 per year depending on your car’s fanciness.

The money is already going to work the way it’s supposed to: almost $2 billion each for local streets and state highways, and almost a billion for transit. Here’s a state website disclosing how it’s being used in each community.

But while this hike had bipartisan support, it was only a minority of Republicans who supported it, and so predictably this opportunistic conspiracy of grifters decided this year to seize on it as their signature issue. Screw having roads and bridges, or seniors being able to walk on sidewalks. All I can possibly be expected to care about is what I pay at the pump! (And Republicans are openly saying they hope this will motivate their otherwise-depressed voters to come out for Congressional elections.)

In addition to vetoing the SB1 revenue, Prop 6 would also change the state constitution to make it even more anti-tax: every increase in gas taxes or vehicle fees would have to go to the ballot, and the Legislature would be barred from passing such measures even when it can muster a two-thirds majority.

Props 5 and 6 in conjunction are our state equivalent of the Trump tax cuts: I’ve got mine, everything else can go to hell. Let’s take these two initiatives, put them in a box, run a bulldozer over the box, take the box’s remains, and set them on fire.

Proposition 3, the Water Supply and Water Quality Act: Dual recommendation – Yes for impact; No for governance

I went back and forth on this for a long time. In the end I had to craft a new kind of dual recommendation.

This is another bond measure, raising $8.9 billion. It raises money to fix and improve our infrastructure for collecting, channeling, cleaning, and reprocessing water for drinking, agriculture, and other uses, as well as for cleaning the natural environment, especially where it affects water flow and safety, but also where it affects wildlife habitats.

It divides its money across several specific agencies for several specific, named projects: restoring SF Bay wetlands; repairing the Oroville dam; funding water systems in disadvantaged communities; restoring Sierra forests; and so forth. It is not really disputed that most of these are worthy causes, but there are problems.

The first problem is the “who pays” question. Overall, even this amount is small compared to the $30 billion per year we spend collectively on water. But a number of these investments – dams and levees, reservoirs, etc. – directly benefit rich agricultural interests that turn the system’s water into cash crops. In an ideal system, a lot more would be asked of them in user fees.

The second problem is that the proposition is so full of sweetheart measures it resembles Tinder. Its proponent, Jerry Meral, used to work for the state but now acts as a policy entrepreneur. He wrangled many established interests to make a bond that would provide something for everybody’s pet project, regardless of merit. One of its worst boondoggles is $750 million to repair the Friant-Kern canal, whose current damage comes from agricultural mismanagement; a smaller-dollar but more offensive section makes sure that some particular water agencies would no longer have to pay into the state greenhouse gas cap-and-trade fund. Possibly related to the coalition making choices like this, key environmental groups like the Sierra Club were completely cut out of the process, and are now in loud opposition.

As part of this problem, it raises real concerns that its spending is unaccountable. Usually, measures like this leave some limited authority for the Legislature to reallocate money depending on what is proving effective or ineffective, commonly requiring a two-thirds majority and always requiring consistency with the stated intent of the statute. I searched all its 25,000 words for references to the Legislature or amendments, and found nothing that would indicate the legislature has any such authority. The money just goes out and year after year, making the recipients – most often state departments, sometimes local water agencies or other independent authorities – practically tin gods that nothing but a new ballot measure can wrest the money from. The Legislature does have the ability to audit the spending, and elected officials have other avenues of control over these agencies, but regardless, this is just a shoddy way to govern!

Still, accepting all these critiques, I’m not sure if the many worthy projects in this list are realistically going to happen other ways. Maybe wealthy interests ought to pay more, but I don’t see a political movement in the medium term sparking such a major realignment of power in water policy. Which I know is kicking the can down the road, but we have a lot of other cans in front of us right now, so to speak. Given the many infrastructure deficits obvious right now, I worry that a principled “no” vote, saying to the proponents “Try again and do better”, while justified, might look later like making the perfect the enemy of the good.

Proposition 12, the Prevention of Cruelty to Farm Animals Act: Yes

This measure would significantly extend humane protections for three farm animals: egg-laying chickens, breeding pigs, and veal calves. By 2022, it would require that eggs sold in the state come from cage-free chickens; that pork be birthed by sows with at least 24 square feet of space; and that veal come from calves with at least 43 square feet of space.

There was already a successful proposition in 2008 that imposed the basic standard that these animals must have enough space to turn around, sit down, stand up, and extend their limbs; however, as it turned out, the combination of vague writing plus only empowering local law enforcement agencies made it difficult to enforce. Also, it only banned practices in-state, not food from out-of-state made using the same practices, forcing the Legislature to pass a companion law for eggs to put producers on a level playing field. In addition to making the space standards more objective, Prop 12 would empower state agencies to enforce them.

The motivation for targeting these three animals seems to be that they are the ones with the most disturbingly tight confinement practices. I agree it is not necessarily wrong to eat animals, but given their dependence on us, treating them humanely is the least we can do. It is well within our financial means: the space standards for egg-laying chickens came into full effect in 2015, and while that did slightly increase the price of eggs, we barely felt it.

Also, practically, concentrated animal feeding operations, it turns out, are not just inhumane, they are also bad agricultural business, part of a flawed market that pushes inevitable consequences such as disease off to the side . So even from a business perspective, these standards likely would have come sooner or later, either voluntarily or by force of law.

Technically, this measure could have been passed by the Legislature. However, in practice, passage would have been unlikely given the sway of agricultural interests there, so it does not trip my “anticlutter” alarm.

Proposition 7, the Daylight Saving Time Repeal Act: Yes

This is the least controversial measure going through this year, with no spending expected on either side.

The name is confusing: it does not repeal Daylight Saving Time. Rather, it takes away an oversevere part of California law preventing any experimentation with DST. For short, think of it as a measure to keep you from having to consider and vote on other measures on the same subject later.

The longer story is that California came early to DST, as a peacetime measure at least. The voters passed the Daylight Saving Time Act in 1949, making the time change more or less as it does now. Because it’s an initiative statute, it cannot be changed without another popular vote – it contained no ability for the Legislature to amend it, even by two-thirds.

Then, the federal government stepped in. The Uniform Time Act of 1966 gives states two choices only: DST or no DST. It also sets the dates of DST if there is any, which Congress extended to eight months of the year starting 2009.

Recently, we have been reevaluating DST and wondering if it’s all it’s cracked up to be. The energy-saving arguments may have been mistaken, and the time change itself causes some harm through disruption. But there’s a better case for just extending it year-round: lighter evenings mean more social activity, more economic activity, and possibly even less crime.

Maybe this is a good idea, maybe it isn’t, but if we want to consider any kind of change, we’re in a double straitjacket right now. First, Congress would need to vote to give the states more flexibility; and second, California could not take advantage of any such flexibility without changing the DST Act at the ballot box. (Indeed, right now we couldn’t even take advantage of our one federally-granted option, eliminating DST as Arizona has.) Prop 7, therefore, would repeal the DST Act as it exists now, and give the Legislature authority to set our time, but only with a two-thirds majority.

Under Prop 7, if enough debate led to enough consensus, the Legislature could take us off DST, and if federal law also changed, the Legislature could extend it year-round or do something else. This ability is a good thing: we should loosen the straitjacket and let our elected policymakers make policy.

There are two potential reasons you might vote no: (1) if you think DST is perfect as is, and want to keep it as hard as possible to undo it; or (2) if you don’t care for DST but also fear a cycle of experimentation, where the Legislature tries one thing, finds problems, then tries another thing, and another, adding complications to your life you don’t need. I myself doubt that would happen, and feel the risk is minor compared to the positive potential of opening up this calcified policy domain.